The Duck Path

The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway was engineered as a triumph of modern infrastructure, yet its legacy is one of division. Like so many projects shaped under Robert Moses, the expressway privileged cars over communities, carving a deep barrier between Brooklyn Heights and its waterfront. The elevated roadway not only brought noise and pollution, but severed social and ecological continuity—residential streets on one side, open parkland and water on the other. The city has grown around it, but never healed from it.

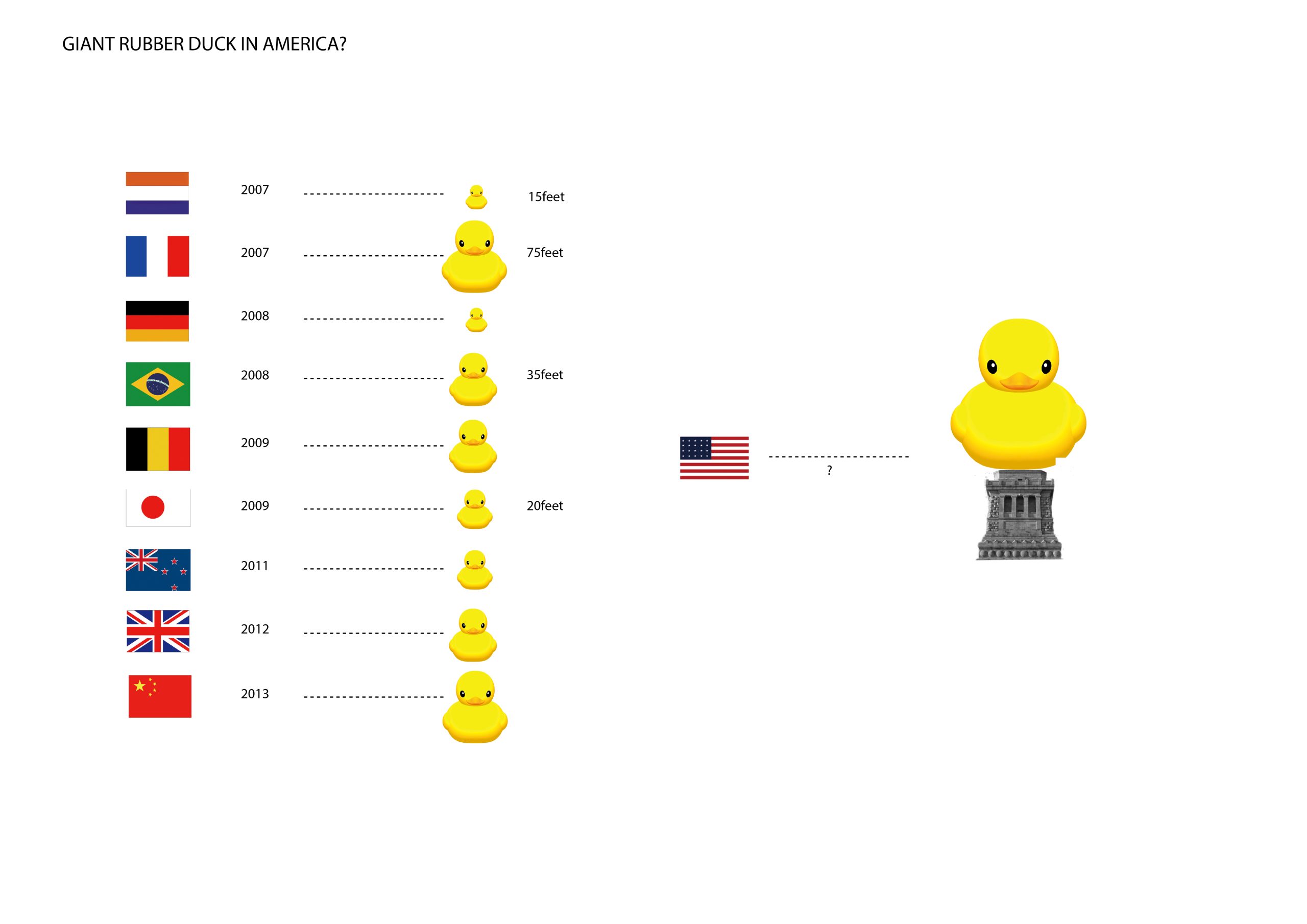

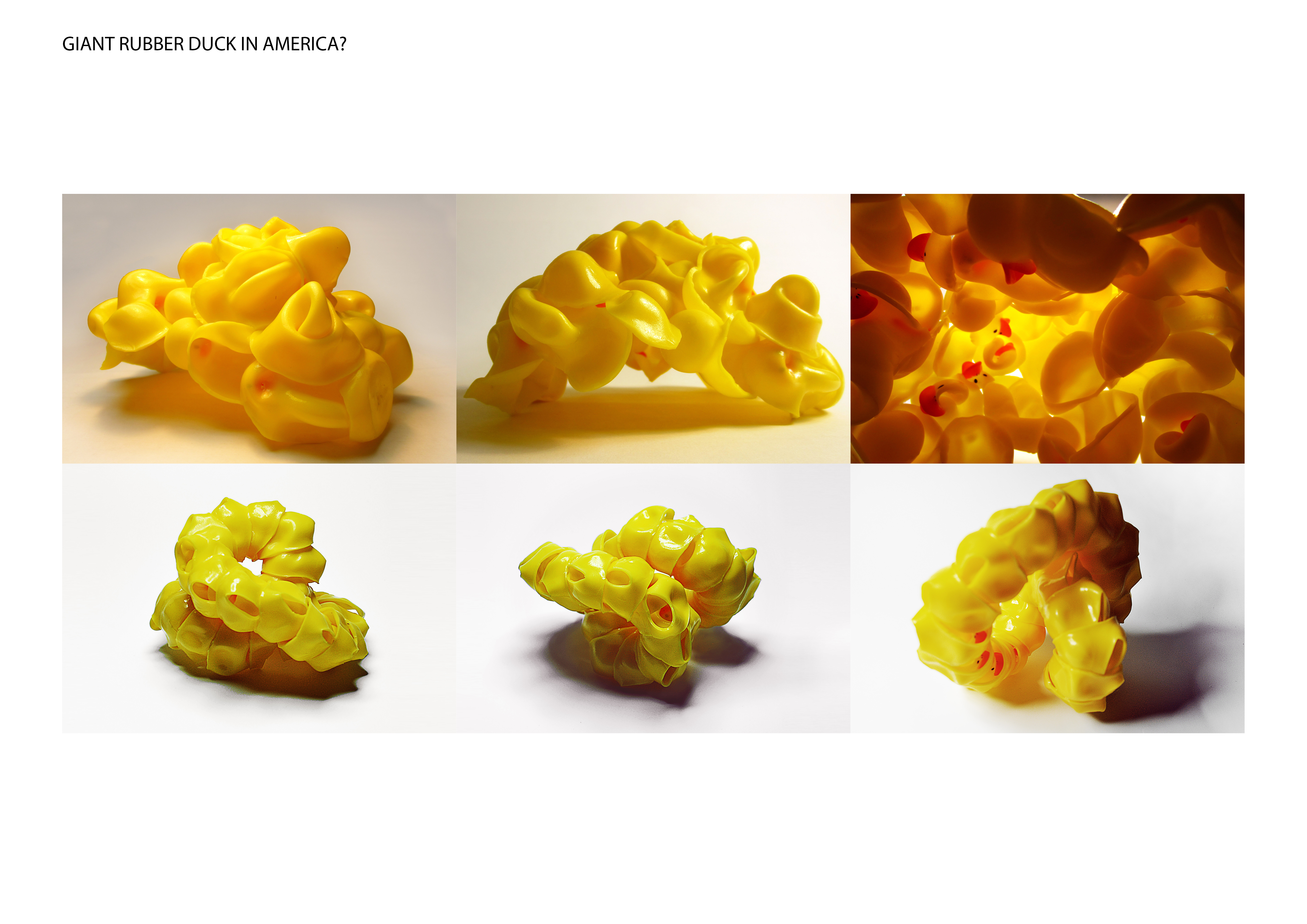

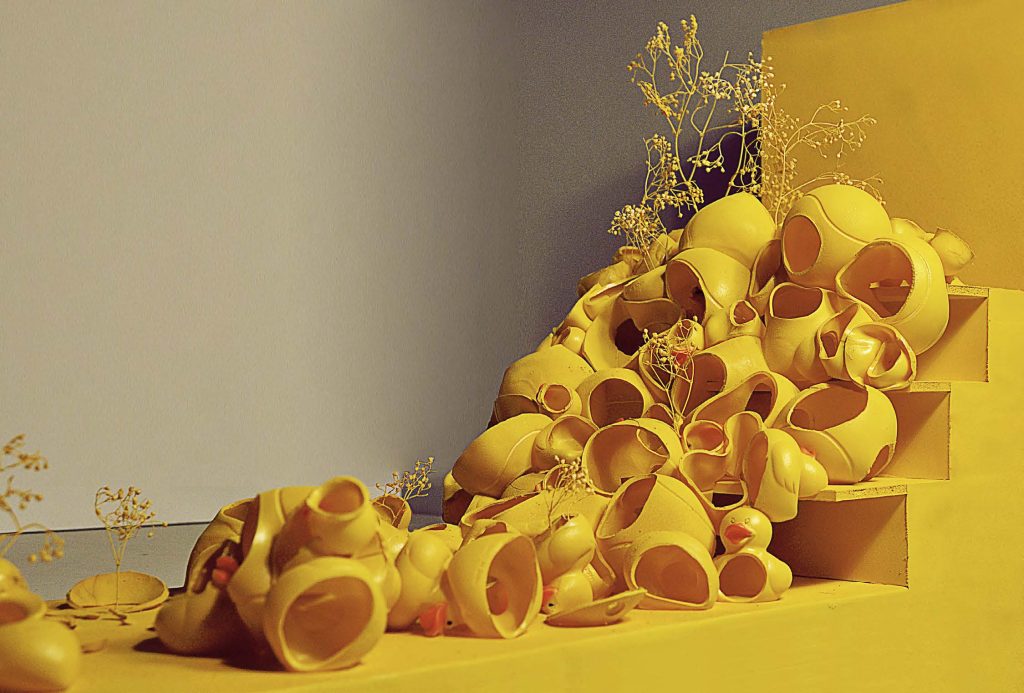

Our project begins with an unlikely urban hero: the rubber duck.

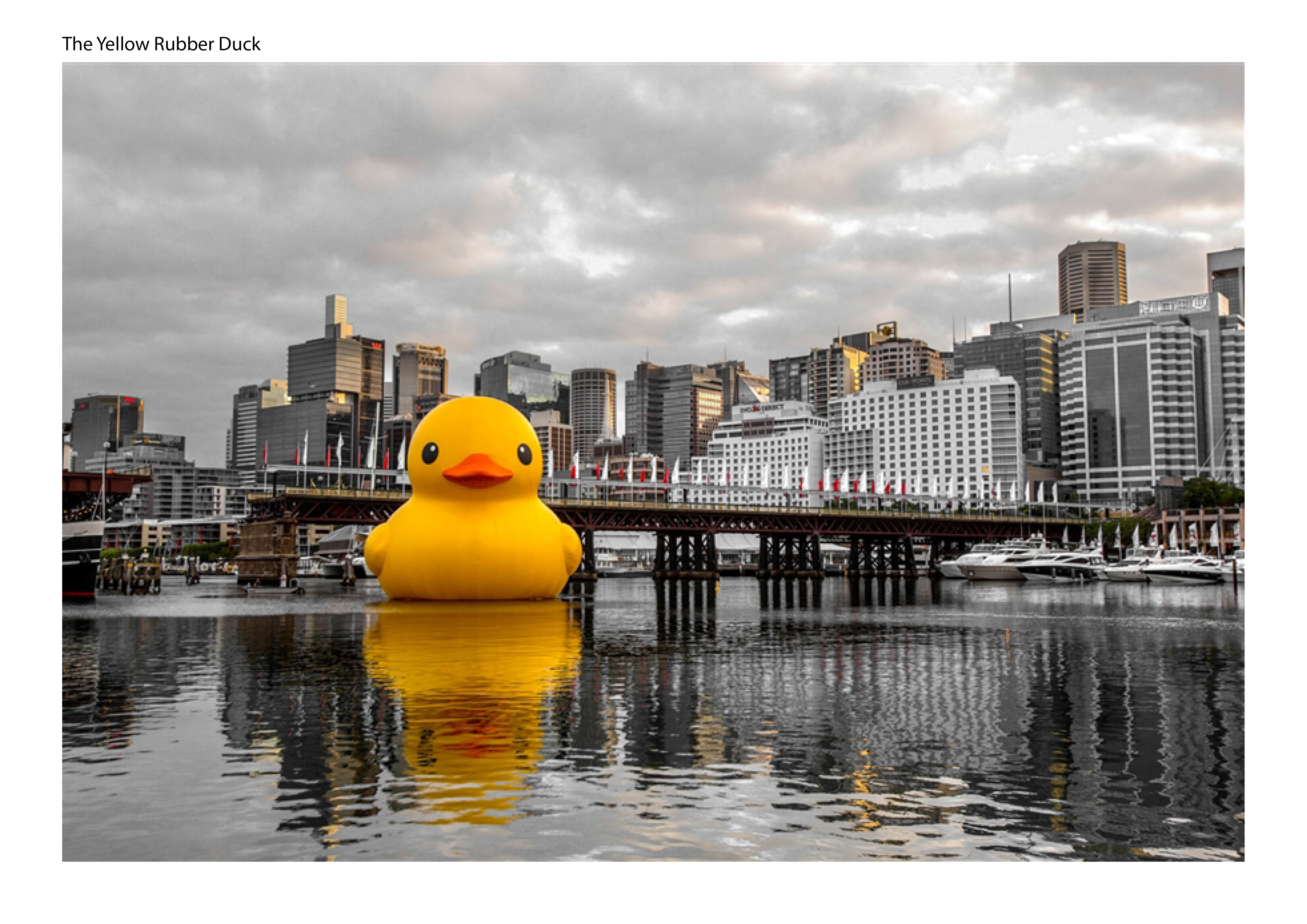

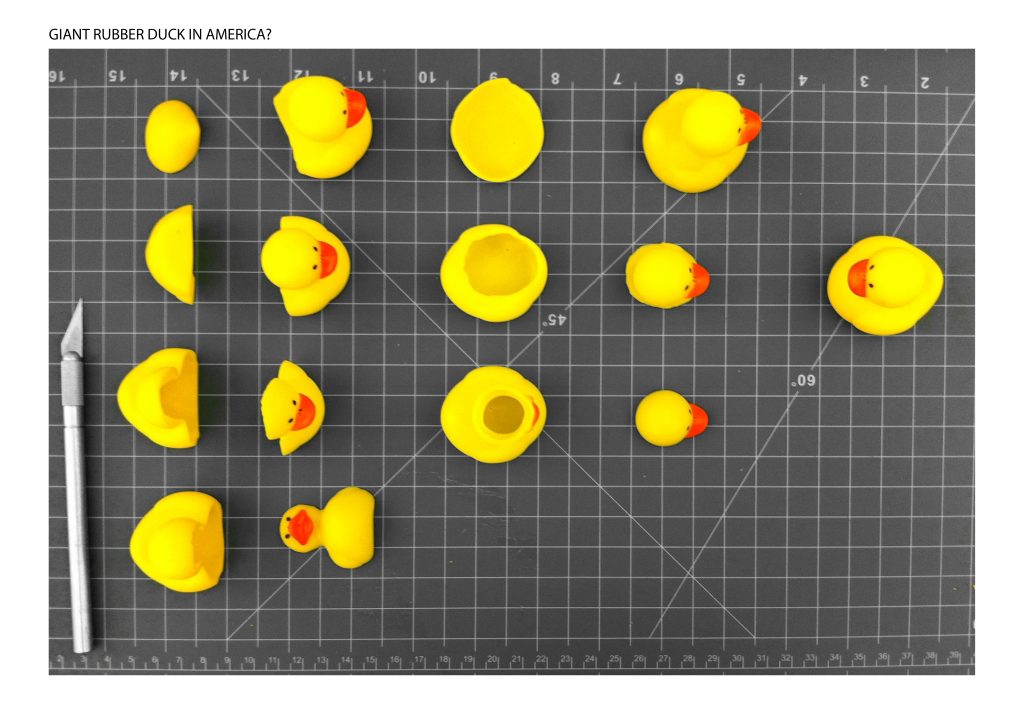

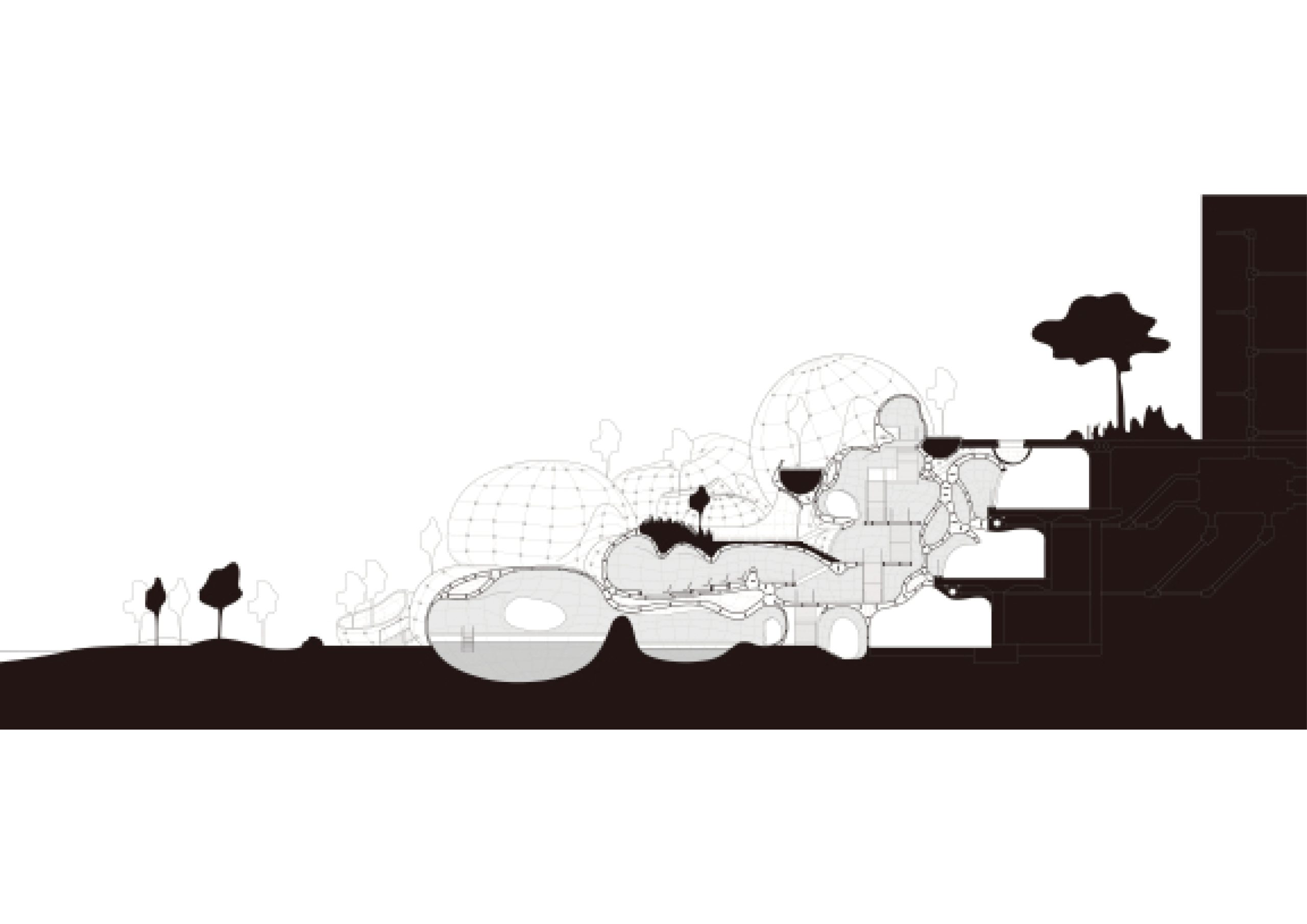

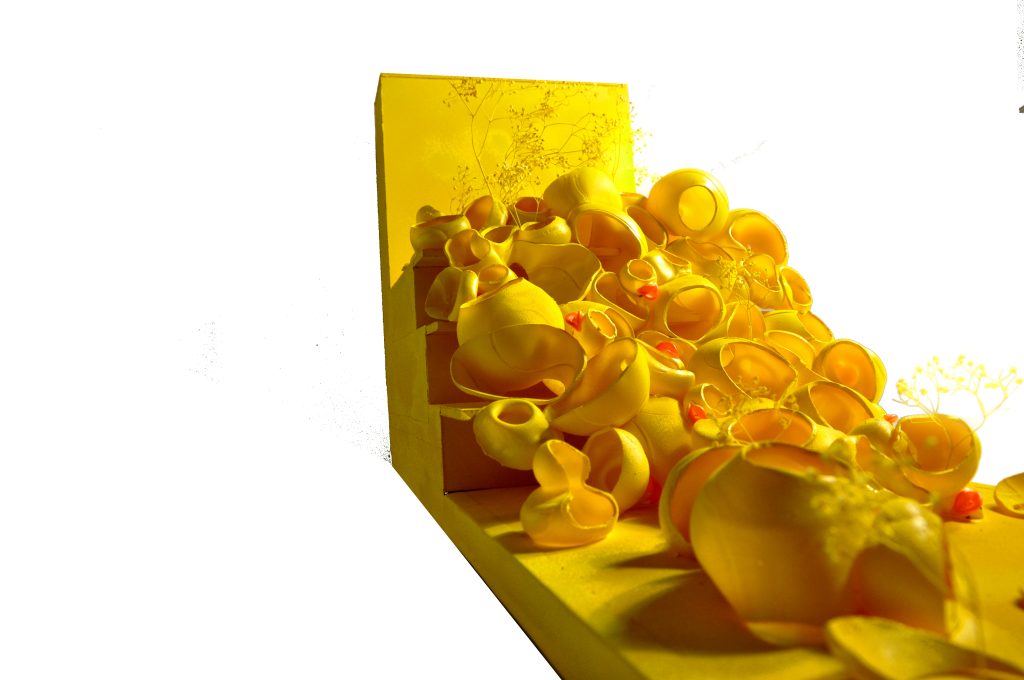

A rubber duck is a familiar symbol—bright, buoyant, playful, and universally understood. But more importantly, it is inflatable: a lightweight structure that takes shape from air. Instead of concrete overpasses and steel girders, we imagined a future connector made from soft, organic bodies—structures that feel alive rather than imposed. From this came a simple idea: sphere-like inflatable volumes, linked together above and around the BQE, creating a new type of urban crossing that feels more biological than infrastructural.

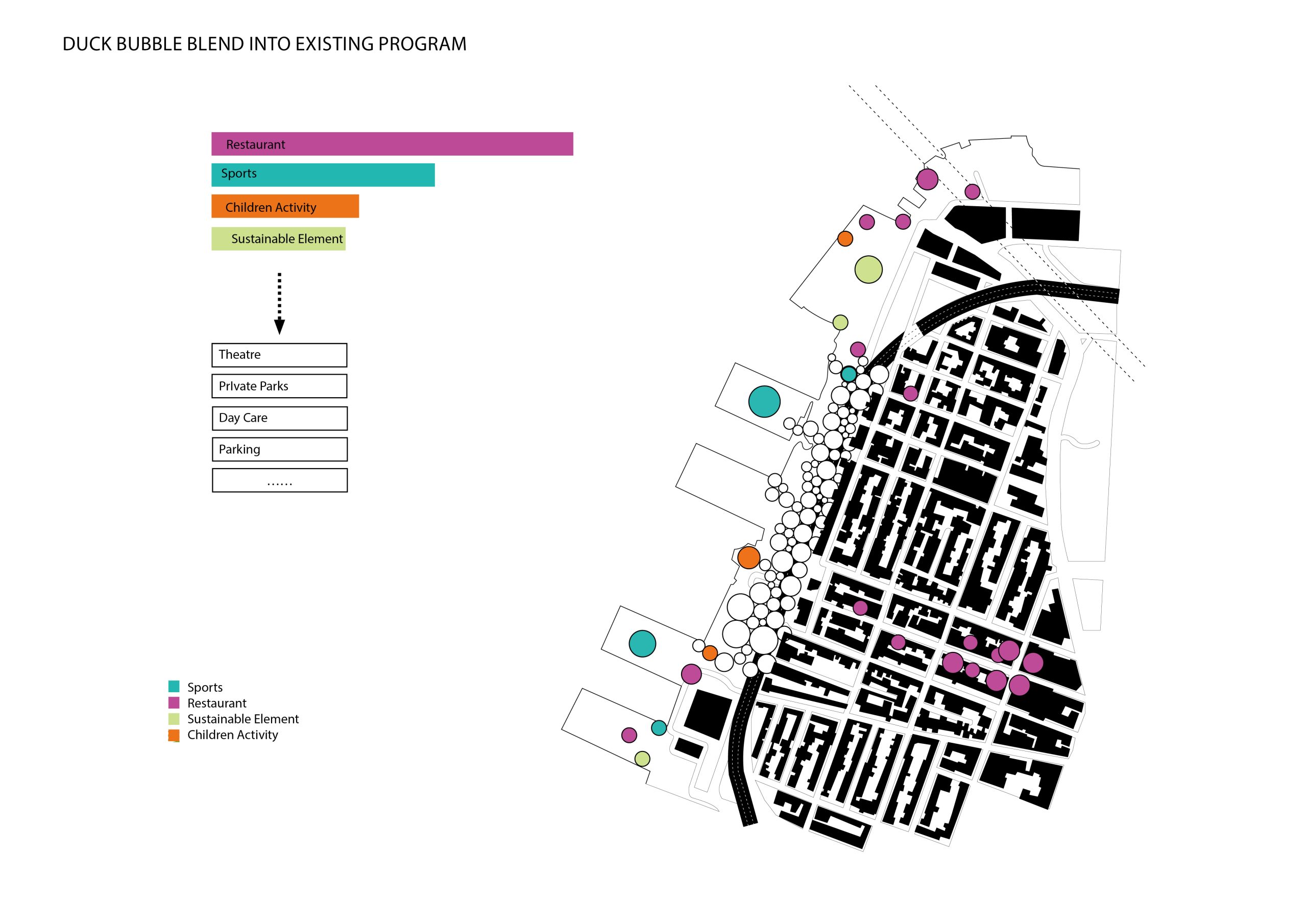

The spheres work as walkable, inhabitable objects—spaces of transition, observation, and occupation. Some stretch across the expressway like inflated bridges; others perch above the highway as viewing pods or micro-parks. Stairs and ramps weave between them, forming a continuous pedestrian ribbon that reconnects the residential district to the waterfront without needing to bury or demolish the freeway.

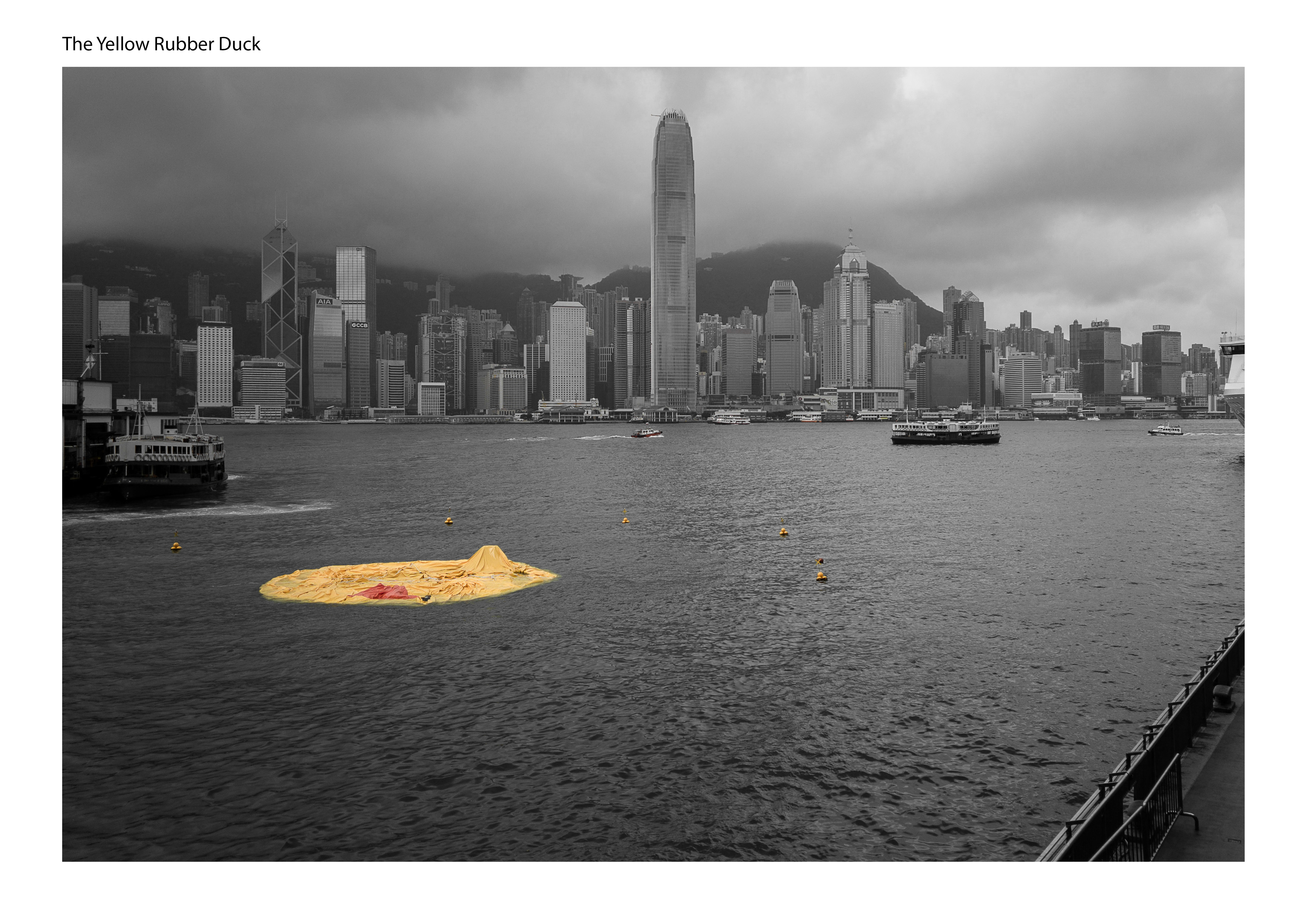

Instead of reinforcing the concrete logic of Moses-era infrastructure, the project softens it, rewilds it, and opens it back to the public. Air-inflated bodies become architectural prosthetics—lighter, reversible, and ephemeral. They repair what the highway broke, not with more highway, but with spatial generosity and whimsical public space.

The concept asks a larger question: if cities are moving toward mega-urban complexity and ecological urgency, why must our future infrastructure look like the past? What if it can grow, adapt, appear and disappear? What if it doesn’t have to dominate the landscape to connect it?

In this vision, the rubber duck is not just a playful symbol—it is a critique of the heavy-handed ambition that shaped the BQE. A reminder that infrastructure can be joyful. A suggestion that connection can be soft, light, and alive. A proposal for a new, more humane relationship between people, parks, waterfronts, and the colossal systems that once tore them apart.

Cornell March Studio (2014)

Collaborator: Xin Jin, Timothy Ho